On January 8 this year, the European-Japanese mission BepiColombo flew by Mercury for the sixth time, making its final gravitational maneuver needed to adjust its orbit so that it can begin orbiting the planet in late 2026. This time, the assembly of both probes and the flyby module slipped only a few hundred kilometers above the north pole of Mercury. Close-up images show potentially icy craters whose bottoms are in permanent shadow, as well as vast sunlit Nordic plains. At 6:59 CET, BepiColombo found itself just 259 kilometers above Mercury’s cool night side. About seven minutes later, it passed right over the planet’s north pole, whereupon it got clear views of the sunlit region near the north pole.

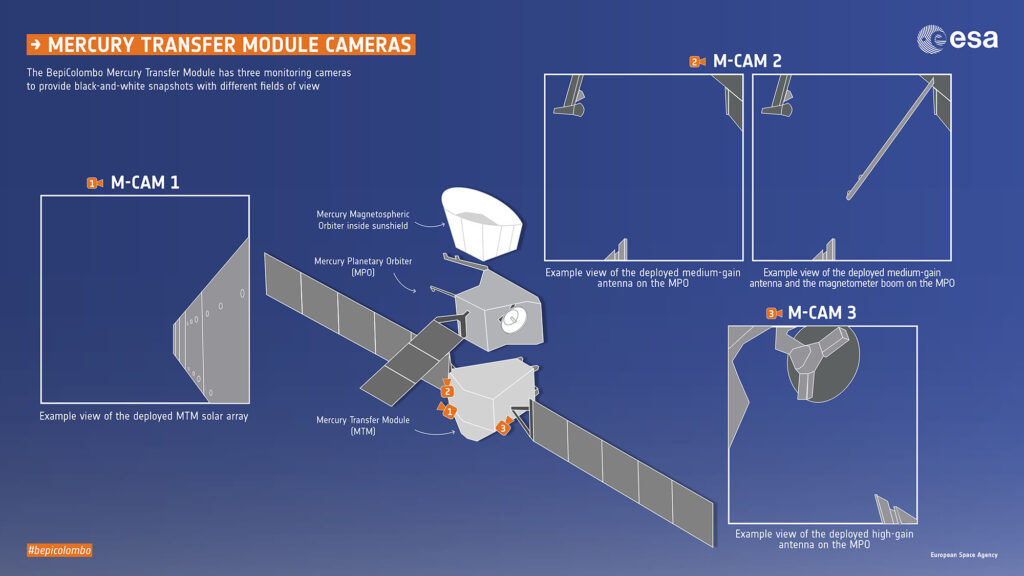

The first image from this flyby was revealed on January 9 by the Director General of the ESA, Josef Aschbacher, as part of the annual press conference. As was the case with previous BepiColombo flybys, the M-CAM monitoring (engineering) cameras did not let us down this time either. This flyby was also the last opportunity for this mission where the M-CAM cameras could take close-up pictures of Mercury. That’s because the flyby module they’re installed on will detach from both science probes — Europe’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Japan’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) — before they enter orbit around Mercury in late 2026.

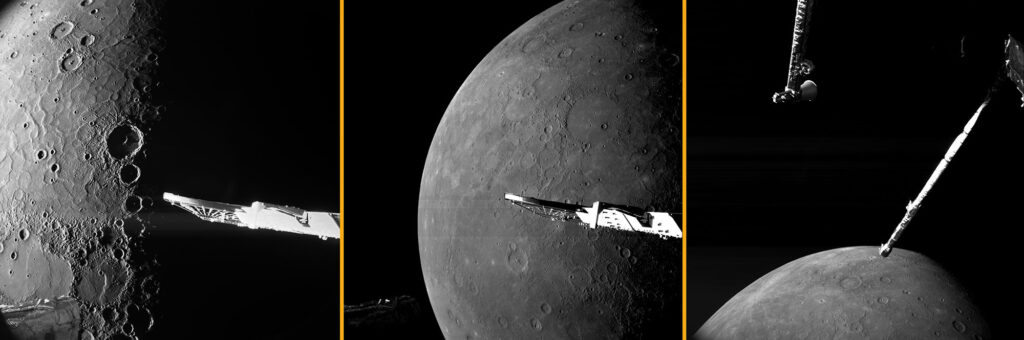

To celebrate M-CAM’s last major event, let’s explore the top three photos from BepiColombo’s sixth encounter with the minor planet and see what Mercury’s secrets they reveal. After flying through Mercury’s shadow, M-CAM 1 got its first glimpse of the planet’s surface. The flyby over the terminator (the interface between day and night) gave the probe a unique opportunity to peer directly below into the permanently shadowed craters at the planet’s north pole. The rims of Prokofiev, Kandinsky, Tolkien and Gordimer craters cast a permanent shadow over their floors, making them some of the coldest places in the entire Solar System – despite Mercury orbiting the closest of all the planets to the Sun.

The great news is that we have evidence that these dark craters contain frozen water. Whether there really is water on Mercury is one of the key Mercury mysteries that the BepiColombo probe will investigate once it enters orbit around the planet. To the left of Mercury’s north pole, in the M-CAM 1 camera view, extend the vast volcanic plains known as Borealis Planitia. These are the smooth plains with the largest area on Mercury, formed by a large-scale eruption of liquid lava 3.7 billion years ago. The lava then flowed into craters such as Henri and Lismer, which are highlighted in the image. Wrinkles on the surface formed over billions of years after the lava solidified, probably in response to the planet contracting as its core cooled.

Another image from M-CAM 1, taken just five minutes after the first, shows that these plains extend over a large part of Mercury’s surface. Mendelssohn crater is clearly visible, its outer rim barely visible above the flooded interior. The smooth surface is edged with only a few smaller, more recent impact craters. Rustaveli crater, further away but still within Borealis Planitia, has suffered a similar fate. At the bottom left of the image is the massive Caloris Basin, the largest impact crater on Mercury, with a diameter of over 1,500 km. The impact that created this basin scarred Mercury’s surface for several thousand kilometers, as evidenced by the linear troughs that extend from it.

Above one exceptionally large trough, a brighter, curved feature resembling a boomerang is visible on the surface. This bright lava flow is likely connected to a deep magma trough beneath the surface. It appears to be similar in color to the lava at the bottom of the Caloris Basin and the lava from Borealis Planitia further north. Another mystery that BepiColombo should solve is where this lava was flowing: into the Caloris Basin or out of it?

Although it may not always appear so from the M-CAM images, Mercury is an exceptionally dark planet. At first glance, its cratered surface may resemble the Moon, but Mercury’s surface reflects only two-thirds of the light. On this dark surface, younger features appear lighter. Scientists do not yet know exactly what Mercury is made of, but it is clear that material brought up from the subsurface gradually darkens with age.

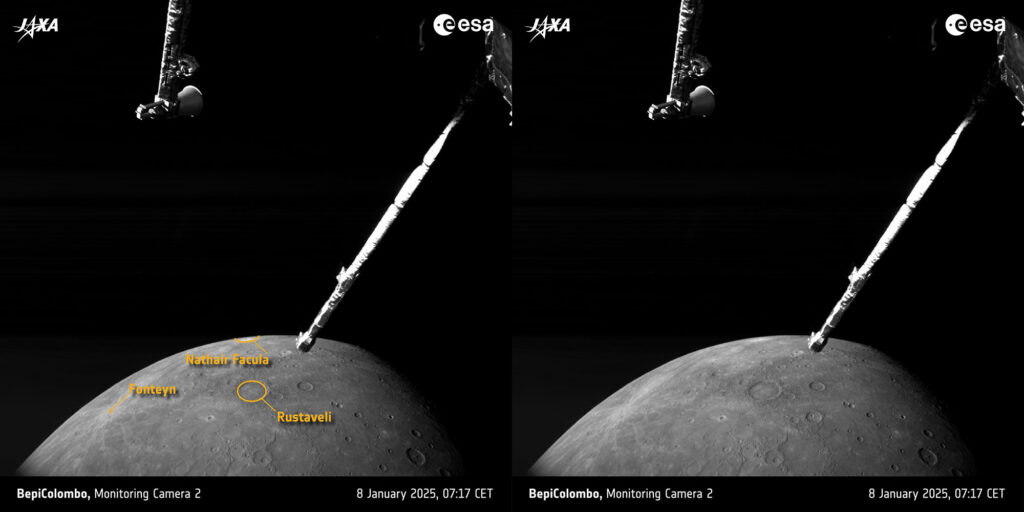

The third featured image from BepiColombo’s sixth flyby was taken by the M-CAM 2 camera and shows impressive examples of two things that bring bright material to the surface – volcanic activity and large impacts. The bright spot near the top of the image is Nathair Facula, the remnant of the largest volcanic eruption on Mercury. At its center is a volcanic vent about 40 km in diameter, which was the site of at least three large eruptions. The explosive volcanic deposit is at least 300 km in diameter. On the left is the relatively young Fonteyn crater, which formed “only” 300 million years ago. Its freshness is evident from the brightness of the ejected debris coming out of it.

During the mission, several BepiColombo instruments will measure the composition of old and new areas of the planet’s surface. This will help us learn what Mercury is made of and how the planet formed. “This is the first time we’ve conducted two flyby campaigns in a row. This flyby will take place a little over a month after the previous one,” said Frank Budnik, BepiColombo flight dynamics manager, adding: “According to our preliminary assessment, everything went smoothly and flawlessly.”

„The main phase of the BepiColombo mission will only begin in two years, but all six flybys of Mercury have provided us with invaluable new information about this little-studied planet. Over the next few weeks, the BepiColombo team will be working hard to use the data from this flyby to uncover as many of Mercury’s mysteries as possible,“ concludes Geraint Jones, ESA BepiColombo Programme Scientist.