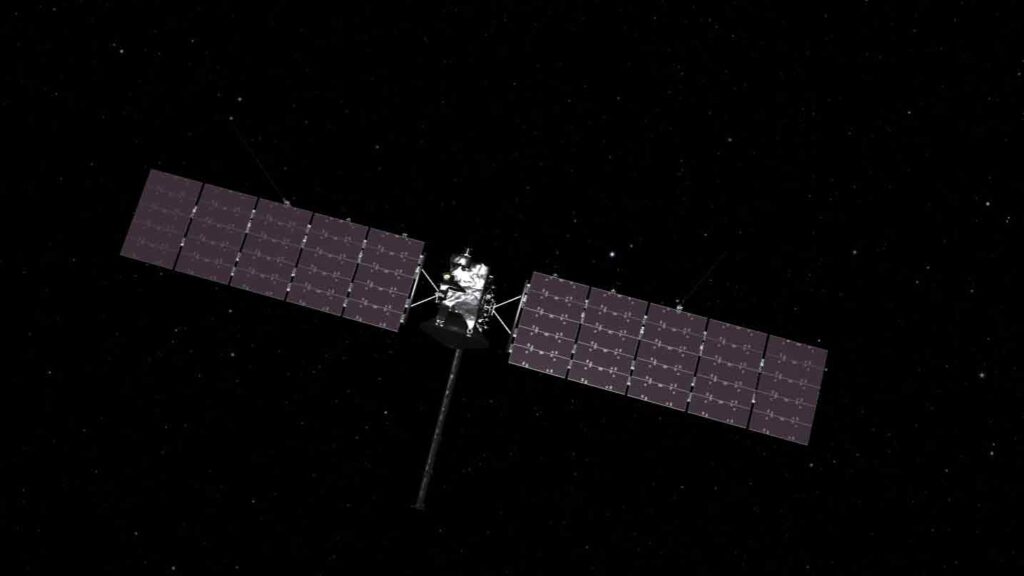

Three months after launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the American Europa Clipper probe still has 2.6 billion kilometers to its goal (entry into orbit around Jupiter in 2030). Once it reaches the largest planet in the Solar System, it will (after the necessary orbital adjustments) begin taking detailed images of the icy moon Europa, using its science cameras. At present, however, other cameras are in the spotlight, whose task is to photograph the very distant surroundings of the probe.

These are two sensors called star trackers. Their images serve the spacecraft as a compass – they help determine the spacecraft’s precise orientation in space, which is critical information for keeping the spacecraft’s communications antennas pointed toward Earth and for the spacecraft to communicate smoothly and two-way with the ground station.

In early December, a pair of star trackers sent back the first images from Europa Clipper from space. The image, made up of three images, captures tiny dots of light, which are stars 150 to 300 light-years away.

The star field captured only 0.1% of the entire sky around the spacecraft, but even taking pictures of such a small part is enough for the on-board computers to determine which way the spacecraft is oriented and whether it should adjust its position in space. The star field captures four bright stars – Gienah, Algorab, Kraz and Alchiba in the constellation Ravenna.

In addition to being interesting for stargazers, the image also confirms the successful operation of the star trackers. Progressive checks of Europa Clipper’s onboard systems have been underway since the spacecraft launched on October 14th of last year aboard SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy.

“The star trackers are engineering hardware that constantly takes images that are processed on board,” says Joanie Noonan, of JPL in Southern California, who leads the mission’s control, navigation and orientation activities. She adds: “We usually don’t download images from the star trackers, but in this case we did because it’s a very good way to verify that the hardware—including the cameras and their optics—survived successfully during launch.

Correctly turning the spacecraft is not about navigation; that’s a separate topic. However, orientation using the star trackers is critical not only for the aforementioned communications but also for the mission’s science activities.

Engineers need to know where the scientific instruments are headed, including the sophisticated Europa Imaging System (EIS) camera array. It will take images that will help scientists map Europa’s surface and explore its mysterious cracks, ridges, and valleys. But the EIS is still under protective covers, which will take at least three more years.

Europa Clipper carries nine scientific experiments and can also use its telecommunications equipment to measure gravity. During 49 flybys of Europa, these instruments will collect a variety of data that will provide scientists with information, such as whether the moon and its internal ocean offer conditions suitable for life.

Europa Clipper is currently 85 million kilometers from Earth and is moving at 27 kilometers per second relative to the Sun. On March 1, the probe will skim past Mars, whose gravity will adjust its orbit around the Sun and speed it up. The Europa Clipper is scheduled to fly past Earth on December 3, 2026, and then the probe will head straight for Jupiter.